|

Winter Customs in Romanian Villages

by

Joyce Dalton

Few people in today's world maintain and cherish their age-old customs, as do the villagers of Romania.

Hardly a week goes by without a religious or secular festival somewhere in Romania. Some of the best, however, take place

between Christmas and New Year's.

For the grandest winter spectacle, head to Romania's northwestern corner by December

27 when the "Festivalul Datinilor de Iarna" (Winter Customs Festival) takes place in the town of Sighetu Marmatiei.

Masks

hang from lamp posts and people pack the streets. More masks‹part demon, part animal, part indescribable‹hide

the faces of young men who run through the streets as oversized cowbells hanging from their waists clang loudly. Far from

idle Halloween fun, masks, here, are an old tradition, symbolizing fertility, the passing and renewal of time and the good

and bad aspects of human nature. By the time the procession gets underway, everyone has caught the excitement and the anticipation

matches that of teens at a rock concert. Accompanied by music and "colinde" (carols), some 40 to 50 groups, representing virtually

every village in Maramures, pass along the main street. All are in traditional dress, meaning, for girls and women, stiff

white blouses with fancy work and puffy sleeves, white or flowered skirts partially covered by striped woven front and back

panels, headscarves, embroidered black woolen vests, thick knee-high socks, a stiff ballet-type shoe called "opinci" which

laces criss-cross fashion over the socks, and white or black wool jackets. Large homemade bags, usually of a black and white

checked design, hang by long twisted wool from shoulders. Some walkers reach into these bags to toss rice or grain toward

the viewers which represents both prosperity and ridding oneself of bad fortune. Boys and men don similar jackets or a white,

long-haired cloak, wide white pants, loose shirts, tooled leather belts, boots and tall hats of curly black or gray wool.

When

a group reaches the reviewing stand, they earn a few minutes in the spotlight for a carol, a folk dance or a tune on old instruments

such as the "trambita," an extremely long horn, or the "buhai," a small barrel through which horsehairs are pulled. Some young

men ride beautiful horses with evergreen and ribbons braided into the mane and tails and red tassels hanging from the bridle.

Gorgeous handmade saddle cloths are ablaze with patterns of colorful flowers. Signaling the end, a horse-drawn sleigh filled

with white-jacketed youths, musicians and of course, Santa Claus passes by the crowd. Throughout the afternoon, folk musicians,

singers and dancers perform from a stage set up by city hall.

In many villages, especially in the northeastern province

of Moldavia, December 31 is the big day — not eve, mind you, but morning. The tradition-packed outdoor event I observed

in Verona, a 45-minute drive from the city of Suceava, is typical. The weather may have been chilly but neither participants

nor onlookers seemed to notice. First, a choir of schoolgirls sang old carols. Animal skin winter jackets failed to completely

hide their embroidered blouses, flowered belts and long striped skirts from which the lacy edge of white under-skirts peeked.

Colorful hand-woven shoulder bags and black head scarves completed the costumes which are unique to the area.

Soon,

this idyllic scene gave way to the whistles and shouts of young men who galloped out for a spirited dance of the "caiuti,"

or horses. With amazingly fast foot movements, punctuated by high kicks and boot-slaps, they maneuvered themselves and white

cloth horse heads, attached to their waists and adorned with embroidery, tassels and a multitude of colored pom poms, around

the small space. In olden days, white horses were believed to be messengers bringing life and luck and this dance symbolizes

the bond between farmers and the animals that pull their wagons and aid in working the land.

A clack, clack, clack

signaled that the "capra" (goat) was coming. A guaranteed crowd pleaser, the carved wooden head is attached to a long pole

which the bearer manipulates to noisily open and close the mouth as he dances around. Any resemblance to a real-life animal

has been disguised with long ribbons, a towering headdress and whatever other adornments flash into the creator's mind. This

dance once foretold an increase in shepherds' flocks along with abundant crops in the new year. Today's antics are lighthearted,

with many a satirical reference to the manners and morals of the villagers. Another festival staple is the dance of the bears

(the two-legged costumed variety). Accompanied by their Gypsy trainer and a youth beating a tambourine-type instrument, the

animals crawl through the crowd. Reaching the center, they perform a dance until eventually, the bears fall dead on the ground.

After their hearts are taken by the trainer, they return to life, theoretically, a more gentle one. Even today, more bears

exist in Romania's Carpathian Mountains than any other place in Europe and this ancient rite suggests the power of man to

tame nature. Throughout the festival, masked figures ran about, banging anything that made noise, to frighten away any stray

bad spirits that might have invaded the merrymaking. This is another reference to pre-modern days when people believed that

spirits of the deceased wandered the Earth between Christmas Eve and January 6. After young orators offered rhyming chants

of welcome and good wishes for the new year, the mayor presented round braided loaves of bread, symbolizing abundance and

rich harvests, to each participant as well as to a Senator or two, who, true to the nature of politicians worldwide, knew

the wisdom of appearing at public events.

Following the spectacle, in a scene repeated in villages and cities throughout

Moldavia, groups of children, dressed as bears, horsemen or Gypsies, made the rounds of their neighborhoods. Announcing themselves

with a jangling bell, they touched the homeowners with a flower-adorned stick while chanting a verse invoking them to be "strong

as stone, quick as an arrow, strong as iron and steel." In return, they received fruit, candy, a pastry or some coins.

For

those whose winter travel plans lean toward more tropical climes, Romania offers many more festival opportunities. One of

the most well-known, "Targul de Fete," or Maidens' Fair, takes place in July atop Mount Gaina, situated about 20 miles west

of Campeni in the province of Transylvania. In decades past, the festival served as an opportunity for young men to meet girls

from neighboring villages (and vice versa, of course). Since this not infrequently led to marriage, everyone dressed in his

or her finest traditional attire.

With today's less isolated lifestyle, young people no longer need an annual event

to meet. Happily, though, the festival lives on and remains a time for traditional garb, food, music and dance along with

appearances by some well-known folk artists.

For another colorful traditional event, in an even more splendid wooded

mountain setting, don't miss "Hora la Prislop." Held mid-August at Prislop Pass, situated along the northerly road which connects

Maramures with Moldavia, this festival attracts people from numerous regions who come, decked out in folk costumes, to mingle

and enjoy the traditional music, songs and dance. Travelers often chance on religious celebrations. The majority of people

belong to the Romanian Orthodox faith and it is not uncommon to come across processions of worshipers carrying flowers and

icons to a church or monastery in honor of a significant event in the church calendar. In villages, such people most likely

will be in traditional dress.

A major religious event takes place annually on August 15 near the Maramures village

of Moisei. Villagers from around the county make pilgrimages to Moisei's monastery for the Feast of the Assumption. Walking

in village groups, sometimes for two days or more, the worshipers carry crosses and holy pictures. The majority of walkers

are children and young people. In a scene reminiscent of first Communion, little girls wear pretty white dresses with white

flowers, headbands or ribbons adorning their hair. Traffic along the narrow roads slows to a crawl as drivers wait their chance

to pass these singing, joyful groups.

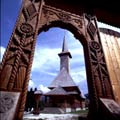

After leaving the main road,

the procession continues another mile and a half up a moderately steep dirt and rock road before reaching the spacious grounds

of the monastery. Most groups arrive on the 14th so the grass is covered with clusters of people who have spread blankets

out and are enjoying the chance to socialize and catch up on news from neighboring villages. Some gather in a long open-fronted

shelter which has been set up for the pilgrims. Even a few vendors have established temporary shop, hawking food and trinkets.

Surprisingly, most of the latter are completely unrelated to religion. Many, especially the elderly, kneel in prayer before

various icons set up around the grounds. Others worship in a small wooden church, typical of the region, dating to 1672 or

in a larger, modern church nearby. On the 15th, priests lead special services for the thousands who have gathered in the wooded

setting.

With its mountains, forests, medieval sites and traditional villages, Romania is a beautiful and rewarding

destination at any time. By planning your trip around a festival, however, you'll come away with a better appreciation of

the Romanian people and their unique culture. And or course, you'll return home with great photos, too.

Painted Eggs

The most readily recognizable examples of Romanian art

are the famed painted eggs, especially prominent around Easter time. Painting of real hollowed-out eggs was an integral part

of preparations for this festival of renewal. Women and children gathered in someone's home and spent a day painting and gossiping.

Intricate patterns were actually secret languages known only to residents of the regions where they were painted. The oldest

known were painted with aqua fortis (nitric acid) on a traditional red background. They're available in nearly all shops and

street markets.

Romania Traditional

Romanian Dolls

Romanian Glass

Romanian Hardy-Antiques

Textiles

At the edge of the street market adjacent to Bran

Castle is a peasant cottage with a window behind which an old woman sits at her loom weaving and watching the passing scene.

She'll invite interested visitors into her home, where her English-speaking daughter will explain that she's 74 years old

and has been weaving since she was seven. She still weaves with thread she spins herself from sheep her family keeps in their

tiny enclosed courtyard. On view in her tiny weaving room, which is also her bedroom, is a selection of magnificent throws

and spreads that she has woven. Not for sale, they're priceless examples of this enduring way of life.

Textile weaving

is the most widespread craft in Romania, handed down from generation to generation, using distinctive family patterns along

with those specific to different districts. Looms still are common in homes and women weave and embroider from childhood through

old age. The predominant fibers, wool and cotton are woven into rugs, wall hangings, table covers and clothing. Some Romanian

weavers and embroiderers still work with threads and yarns they produce themselves, but younger weavers tend to purchase their

raw materials. They weave and embroider just about every cloth article used in their homes, from colorful linen and cotton

towels to window draperies, bedspreads, rugs, wall hangings, furniture throws and clothing. In a village near Sibiu, part

of a bride's dowry is still a tolic, used to decorate horses of those who ride from house to house issuing wedding invitations.

Embroidery

on folk costumes worn for holidays and special occasions (like weddings) follows strict regional patterns and serves also

as a sort of secret language known only to people within the different regions. Sibiu uses graphic black and white motifs,

reflecting its Saxon heritage; southern regions of Arges, Muscel, Dimbovita and Prahova use red, black maroon, yellow, gold,

and silver threads, reflecting influences of the Ottoman Empire. Buzau uses terra cotta; Oas uses green and Moldavia uses

orange and the Voronet blue made world-famous by its use on the monastery of the same name. Especially beautiful is cut embroidery

on white or ecru linen and cotton, done throughout the country.

Rugs

While

technically textiles, these deserve their own category, because no other textiles so dramatically reflect their regions of

origin. As varied as different areas' attractions, so too are the rugs that are displayed on surrounding fences. Most are

flat-weave kilims, probably introduced centuries ago by the controlling Ottoman Empire. Today's hand-weavers mix traditional

vegetable-dyed yarns with commercial aniline-dyed yarns to produce startling accents within traditional patterns and colors.

Rugs from Oltenia reflect nature, with flowers, trees and birds. Those of Moldavia have patterns of little branches repeated

in rows to create a tree of life. Rugs from Maramures tend to have geometric shapes, resembling those from Turkey and the

Caucasian mountains.

Crafts of Romania

While there are great Romanian fine artists, among whom 20th century sculptor

Constantin Brancusi is probably the most famous, the typical zest for life and almost na´ve optimism that the world is really

a beautiful place seem best expressed in the traditional art and craft of Romanian peasants, extending even to their colorful,

unique grave markers. In the "Merry Cemetery" of Sapanta, in Northern Romania, carved wooden crosses are painted traditional

blue and embellished with fanciful borders, renderings of the deceased and often anecdotes of their lives. As in most parts

of the world, full-time artists and artisans are drawn together, tending to form communities throughout the country, where

locales are aesthetically inspiring and economically viable. Bucharest and a few of the larger towns boast a few galleries

showcasing work from such artist communities, but most don't have galleries. A few examples of local artists' and artisans'

work are shown and sold in town museums, but most is sold in street markets adjoining major attractions. Sellers usually are

also the makers and some of them speak English. A conversation with them can reveal fascinating facets of Romanian culture.

Works of Brancusi are in various locales, but one of the finest collections is in the city of Targu Jiu, in Oltenia province

on the southern border of the Carpathian Mountains. Nearby Horezu is a major center for ceramics, wood-carving and iron forging

and the Horezu Museum of Art showcases some of the best work of past and contemporary artists.

|